Robert Gwathmey

Text courtesy of “Robert Gwathmey: The Life and Art of a Passionate Observer” written by Micheal Kammen discussing Father and Child:

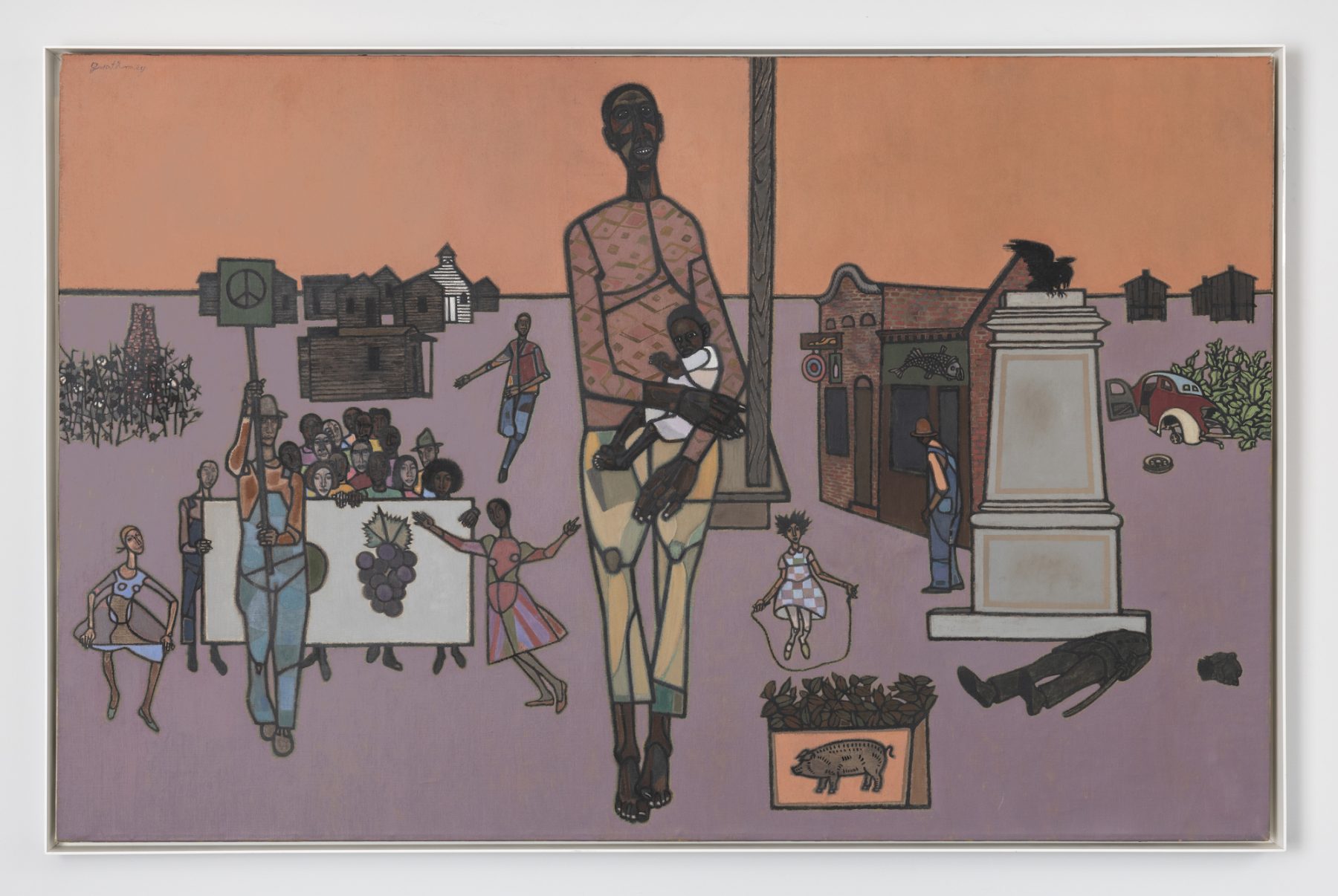

There is, however, one particular stereotype of African American life that Gwathmey took paints to repudiate: the fatherless family or the disintegrating family unit. As early as 1948 in Children Dancing, Gwathmey affectionately called attention to the black family as a complete and cohesive entity. In 1974, however, nine years after the Moynihan report stressed the “single-headed” black family as not merely a terrible legacy of slavery but a pathological situation in contemporary society, Gwathmey painted Father and Child. It is a complex and fascinating work that puts the paternal role as a responsible parent front and center, survivor of an Old South that has been shattered, symbolized by the toppled statue of Johnny Reb (the Confederate soldier), replaced by the ubiquitous black crow, a wrecked car, and woebegone shops. To the left of the loving father is Gwathmey himself (also a loving father) holding up a peace sign with a cluster of people of both races behind him, unified spatially and by the social demonstration they are supporting. If it is a picture of protest, the forces of good appear to have triumphed over regional myths of racial hierarchy and domination. The outlandish color combinations, a salmon sky above a lavender foreground, are vintage Gwathmey. They remind us once again of the aptness in Sherwood Anderson’s words: “If you are a canvas do you shudder sometimes when the painter stands before you? All the others lending their color to him. A composition being made. Himself the composition”

Gwathmey was not alone among the Social Realists in emphasizing the black father as a caring and nurturing figure. Joseph Hirsch, for example, made a beautiful and moving lithograph titled Father and Son in an edition of 250 impressions. Other realists created comparable images. Some of these artists do, indeed, romanticize African American family life, but no more so than mainstream artists romanticized white family life throughout the nineteenth century and especially during the Victorian decades.

Robert Gwathmey

Father and Child, 1974

Oil on canvas

36 x 56 inches

Signed upper left